Residential Investments in Germany – including Berlin Residential Investment Market – June 2021

1. Jun 2021

1. Jun 2021

Dear Reader,

The current legislative period is drawing to a close and Germany’s political parties are gearing up their pre-election campaigns. So, there’s no better time to look back and review the developments that have impacted our industry over the past few years. Unfortunately, rather than having opened the door to lighter regulation, Germany’s politicians have repeatedly legislated to introduce ever more stringent regulations that have affected every facet of the industry. Yes, lawmakers have rediscovered their penchant for interfering in the housing industry, but all too often with the wrong measures. And in the end, it is the tenants who foot the bill. It is clear that we need a new approach – away from stoking divisions between tenants and landlords, and towards a joint dialogue on what contemporary housing should look like, how home ownership can be strengthened and how much housing is worth to us as a society.

Read on to find out more!

Your

Jürgen Michael Schick and Dr Josef Girshovich

Stefanie Szisch | Managing Partner, Vivest

Attacks on real estate companies have become a regular occurrence in Germany’s major cities. Vehicles are set on fire, car tires are punctured, shop windows are smashed, facades are vandalised and employees are threatened and intimidated. My company has also been targeted on an almost monthly basis. Typically, vandals scratch and spray graffiti on our windows, sometimes they even smash them. The signs we put up to advertise sales are regularly torn down and destroyed. The nationwide hostility against our industry reached a disturbing climax when a real estate company’s employee was attacked and injured in her apartment in Leipzig. In most cases, we will never know what motivates such attacks or find out who the perpetrators are.

And because these crimes usually involve damage to property, the outbreaks of violence can easily be dismissed as the youthful indiscretions of a handful of idealistic to ideological activists. As a result, many of the companies that have been targeted have decided it is better to stay quiet, say nothing, and decline to press charges. Drawing attention to the attacks, companies reason, would only embolden the perpetrators and attract copycats.

At the same time, I can certainly understand many people’s current sense of frustration. There is a housing shortage in Germany’s largest cities and conurbations. Middle-income households, and public-sector workers in particular, frequently find that a new apartment is beyond their financial reach. Of course, that is frustrating for people who want to move into a new home with their partner, or who are looking for a bigger apartment because they want to start a family. People looking to downsize, maybe because they have separated from a long-term partner, are just as badly affected. Many have no choice but to stay where they are, sharing a home with their former partner. For large swathes of the population, moving home is no longer an affordable option.

There are two things that worry me most right now. First, that some people’s frustrations are boiling over into blatant aggression and, second, that the scapegoats – the real estate companies – have already been so clearly identified. The housing industry is nothing more, and nothing less, than a part of the wider fabric of society. It cannot offer a panacea or create more and more affordable housing all on its own. Nor should it serve as a scapegoat for more universal problems. What we need right now is a dialogue on how we, as a society, can find our way out of this spiral of mutual recrimination. We don’t need blanket judgements and we shouldn’t be hoodwinked by simple solutions. By that, I mean we shouldn’t be incited by the latest demands to expropriate private housing companies, demands that fuel hostility and that a number of political parties have thrown their weight behind. I also mean we shouldn’t accept the arrogant behaviour of some real estate entrepreneurs. The following applies equally to everyone: There is nothing to be gained from finger-pointing. Even more so, seeking to allocate blame will not do anything to ease tensions on the housing market.

There are numerous initiatives seeking to facilitate constructive communication and discourse on the current housing and affordability crisis on the one hand and, more broadly, on the future of urban coexistence on the other. But these initiatives and associations are often small-scale, with narrowly defined goals and interests. Looking at these initiatives, it is difficult to identify a common language or a shared platform. This is where the real estate industry as a whole is called upon to build a platform for exchange, a platform that can facilitate dialogue over the next few years and that can reach out to engage people in the cities.

It is not too late to stop the current radicalisation process. We just need to deploy compelling arguments to make sure that we address the challenges of affordability and housing shortages within the bounds of civil society. But it would be foolish to believe that it is only “the others” who need to make a move.

Marcus Buder | Head of Commercial Real Estate Financing, Berliner Sparkasse

Berlin’s office market has been coping surprisingly well with the fallout from the coronavirus pandemic. Although many employees are still working from home, office take-up has remained fairly stable. Despite numerous completions, the vacancy rate was up only marginally, by half a percentage point to 1.8 per cent, at the end of 2020. This is among the findings of a survey conducted by bulwiengesa for the latest edition of the Berliner Sparkasse market report, which also finds that prime office rents remained stable at EUR 39.00/sqm. The Berlin office market’s remarkable stability is, at least in part, due to its specific historical situation, combined with the city’s diversified economic structure, which is proving more resilient in this crisis than in previous crises. And what applies to the office market is equally true of the city’s residential real estate market.

Compared with the markets in Germany’s other top 7 cities, Berlin’s office market occupies a relatively comfortable and quite unique position. Offices are still in short supply in the capital. No other top 7 city has less office space per capita. Cities such as Frankfurt and Munich, for example, with their many commuters, have more than twice the space available per inhabitant. For historical reasons that stretched over decades, Berlin was unable to develop large inbound commuter flows, so there are practically no reserves on the office property market.

But this structural shortage of office space is only one explanation. The other is Berlin’s distinctive economic structure. Berlin has long been Germany’s number one start-up hub. The New York Times once referred to the city as “Silicon Alley”, cheekily echoing the name given to the undisputed hotbed of tech in the United States, and not for nothing. During the pandemic, as we have seen, the city’s economy is one of its biggest advantages. Historically, the start-up sector has been sensitive to economic cycles, but during this crisis in particular, many start-ups were not only able to weather the storm, they exploited it as a growth accelerator. A host of online fashion stores and food delivery services, for example, have emerged stronger than ever before. And as these companies grow, so does their demand for office space.

Equally crisis-proof (and heavily represented in the capital) is the public sector. The Cologne Institute for Economic Research (IW) calculated that Berlin had significantly more state and municipal employees per inhabitant than any other federal state in 2018. And that is not even including federal employees. In total, there are almost 280,000 public sector employees in Berlin, equivalent to almost one in five employees subject to social security contributions. All of this also supports a veritable troop of other industries that depend on government business, including the media, trade and industry associations, consultants, law firms and many more besides. Being the seat of government serves as an anchor of stability for Berlin, compensating for the lack of large national and multinational corporations that are at home in other capitals.

The robust health of the office market has a positive knock-on effect on the city’s residential market. The high level of job security in the public sector and in downstream services means that there is a significant supply of crisis-proof tenants and relatively secure rental income. Moreover, the “capital” as a place to work has lost none of its appeal for newcomers, nor has its status as an IT hub diminished – quite the opposite. Berlin is and will remain a city that attracts talented young professionals, who, in turn, have a positive impact on housing demand. The only cloud on the horizon is Berlin’s reliance on tourism, which has, understandably, been hard hit by the pandemic. Industries that depend on large numbers of tourists are suffering badly from the ongoing lockdown restrictions. Nevertheless, one thing should give them hope: Berlin will quickly attract visitors again.

Daniel Preis | CSO, Domicil Real Estate AG

The fact that women invest differently than men is no secret. Women’s investment decisions tend to be based more on security, sustainability and transparency. In particular, however, women want to know that they can trust their contractual partners and that, once they have made their investment decision, there will be no nasty surprises: no hidden small print, no additional fees, and no risks that are brushed under the carpet only to emerge later on. Six words they never want to hear are “But you should have known that”.

Now, bear in mind these clear and comprehensible criteria and you are sure to be surprised when you consider the proportion of women who invest in real estate. Only about one-third of all residential purchases made by single individuals are made by women. If women buy real estate, then in most cases it is a joint purchase with their partner. As an investment asset, it would certainly seem as if individual women have little interest in apartments.

For me, this raises the following question: Are women fundamentally less interested in real estate investments than men? Or are many real estate investments so non-transparent and burdened with footnotes that they do not meet women’s expectations of contractual reliability?

Because one thing is clear: Investments in real estate are inherently long-term, which means they are significantly less volatile than stocks and other investment assets, and they are generally highly transparent. Buying an apartment as an investment is, basically, entirely straightforward. Once the purchase has been notarised, the buyer is nothing more and nothing less than the owner of an apartment. Accordingly, residential real estate should be consistently attractive for female investors.

More and more companies are actively embracing the issue of women in leadership roles. In 2021, financial independence for women is no longer a lofty goal, it is the norm. Of course, many issues still need to be resolved, including the gender pay gap and discussions about the introduction of a quota for women in management positions. Irrespective of this, however, the real estate industry should address the question of whether it is making the right offers to female investors and buyers. Fund initiators, banks, insurance companies and many crowd investing platforms have already made significant strides in this regard and have a correspondingly higher proportion of female customers. The fact that this is not the case in real estate in 2021 does not cast the real estate industry in a good light. Not only does it reinforce the industry’s reputation as a men’s club, such a half-hearted approach to the growing number of financially independent and well-educated women who could represent more than 50 per cent of the industry’s potential customers makes no business sense whatsoever.

Jürgen Michael Schick, FRICS | President of IVD, Immobilien Verband Deutschland e.V.

Take a look at the Building Land Mobilisation Act, which was passed after its second and third readings in the Bundestag on Friday and you will quickly realise that the government wants Germany to remain a country of tenants. The last thing Germany’s politicians want is more homeowners. After moves to support homeownership aspirations in recent years, including the help-to-buy scheme for families and reforms to split real estate agent commission payments equally between buyers and sellers, I have to say I am quite shocked. We had already taken the first right steps to promote homeownership. The next steps should have been to exempt first-time buyers from real estate transfer tax and equity guarantees. Particularly in times of low to negative interest rates, these would have been the most appropriate instruments to boost homeownership rates, both for owner-occupiers and buy-to-let investors.

The government, however, has different ideas and its amendments to the German Federal Building Code read like a state-imposed tenant manifesto. I would like to focus on two aspects in particular because, for me, they clarify the two faces of the law – and they need to be understood in context.

On the one hand, the Building Land Mobilisation Act restricts the purchase of rental condominiums. Here, the federal government is playing on the persistent prejudice that tenants are increasingly threatened with eviction if their apartment building is converted into a condominium complex and their apartment is sold to a new owner. But is this really true? Most metropolitan areas with tight housing markets have strict regulations to protect tenants: a protective shield far beyond the scope of traditional tenant rights applies after the sale of any apartment and includes a ban on evictions for own use for seven, ten and sometimes even 15 years. It would be impossible to provide longer-term tenant protection, unless we want to see life-long guaranteed tenancies.

But if this de facto ban on converting rental apartments into condominiums is not intended to protect tenants, what is its purpose? To find out, it is worth taking a look at one of the requirements that need to be fulfilled before any privatisations can be approved. The new law states that an apartment building may only be subdivided if two-thirds of the tenants in a multifamily building exercise their right of first refusal. Since this hardly ever happens in practice, however, it means that tenants have effectively been deprived of any opportunity to buy their own apartments.

And now the second point, the flip side of the coin if you will, which seeks to restrict the private ownership of residential property. While dashing the hopes of potential tenant buyers, the Building Land Mobilisation Act also makes it easier for municipalities to exercise their rights of first refusal. First, the Act extends the period for exercising a municipal right of first refusal from two to three months. Second, municipalities can attempt to pay a lower price for the properties they want to acquire – they are not bound to match any price agreement concluded between the private individuals (or companies) buying and selling the property, but have the right to acquire the property at the “market value”. So, while private homeownership is being made more difficult, municipalities and state-owned housing companies have never had it easier. As the explanatory notes published by the Bundestag committee that scrutinised the legislation frankly state: “Compared to existing regulations, this will, in many cases, create a price dampening effect to the benefit of municipalities”.

The Building Land Mobilisation Act aims to make it more difficult for private investors to acquire residential property and for tenants to get on the property ladder. The major losers from these reforms will be middle-income households who cannot afford high-priced new-build apartments. In effect, the new legislation actively prevents people from making financial provision for their retirement and, as a result, actually promotes poverty among older people across broad sections of the population. At the same time, people are to be forced into a relationship of dependency with the state as their landlord. There is no other way to interpret the deliberate preferential treatment granted to the state over the individual when it comes to acquiring property. For me, the new Building Land Mobilisation Act is a damning indictment of the outgoing federal government’s social and pension policy.

On 15 April, the Federal Constitutional Court declared Berlin’s rent cap unconstitutional. In their landmark decision, the judges in Karlsruhe found that the state of Berlin had overreached its legislative competence and confirmed that tenancy law remains under the purview of federal legislators. However, this does not mean that the spectre of the rent cap has been banished. A quick glance the election manifestos announced by the SPD, the Greens and Die Linke parties are enough to confirm that, if they get an electoral majority in September, Germany’s three main left-wing parties plan to introduce a nationwide rent cap and will permit rents to increase only in line with inflation. However, one thing is already clear: Even though their proposals for a federal rent cap law might be formally permissible, it is highly debatable whether such encroachments on existing tenancy agreements, on freedom of contract in general and on the protection of property rights set forth in Section 14 of the Basic Law would be constitutional.

On 7 May, after months of negotiations, Germany’s parliament, the Bundestag, passed the Building Land Mobilisation Act. The law represents a comprehensive amendment to the existing German Federal Building Code – with two controversial consequences for owners of apartment buildings: On the one hand, the conversion of rental apartments into condominiums will, in future, be subject to official approval. In principle, this means that property owners will not be able to subdivide apartment buildings with more than five units without authorisation (municipalities will also be given the right to reduce the restrictions to buildings with three units, or to increase them to a maximum of 15). Since the list of exceptions for which permission must be granted is very narrow, the restriction is tantamount to a ban: anyone who has not yet converted their rental apartments into condominiums will find it almost impossible to do so over the next few. In addition, municipal authorities’ rights of first refusal will be extended outside of designated neighbourhood protection areas. Moreover, municipalities will be given three months instead of two months to decide whether they want to exercise their pre-emptive purchase rights. In an even more significant change, municipalities will not only be able to step in and buy with the same terms and conditions agreed between seller and buyer, they will be allowed to acquire the property at “market value”. This is likely to lead to protracted legal disputes between sellers and municipalities, as sellers will now have to demonstrate that the agreed purchase price actually corresponds to the market value. There is, however, one small consolation: The federal law will need to be implemented by each of Germany’s 16 federal states – and some, including Baden-Württemberg and North Rhine-Westphalia, have already announced that they will not be making use of these regulations.

With the exception of Berlin, building permit approvals are rising across Germany. Despite the coronavirus pandemic, the number of building permits issued nationwide rose to 368,400 units in 2020, a year-on-year increase of around 2.2 per cent. Over the same period, building permits and completion numbers in the German capital have fallen. In 2020, only 16,000 new units were completed – a decline of 14 per cent compared to 2019. In another concerning development, Berlin’s building authorities issued only 1,094 building permits in February 2021, around 9 per cent fewer than in February of the previous year. The knock-on effects speak for themselves: While the housing market is easing nationwide and rents are no longer rising as sharply, the housing supply in Berlin remains too low – with clear consequences for rental prices in the capital.

Office and commercial building with significant rental upside in Berlin-Lichtenberg

This five-storey commercial property was completed in 1996. The main tenant has been in place since 1999 and occupies the entire ground floor area, plus the first and second floors. The third floor is let to an online retailer. Floors four and five are in a vanilla shell condition and are untenanted.

There are several parking spaces and an underground garage on the 4,007-sqm plot. The property is located in a commercial zone in the Berlin district of Lichtenberg.

Price: EUR 6,900,000 plus 5.95% commission (incl. VAT)

Total lettable area: 4,018 sqm

Annual net rent: EUR 243,672

Information acc. to energy performance certificate: Not yet available / in preparation.

(Please quote property reference 52335 when making your enquiry)

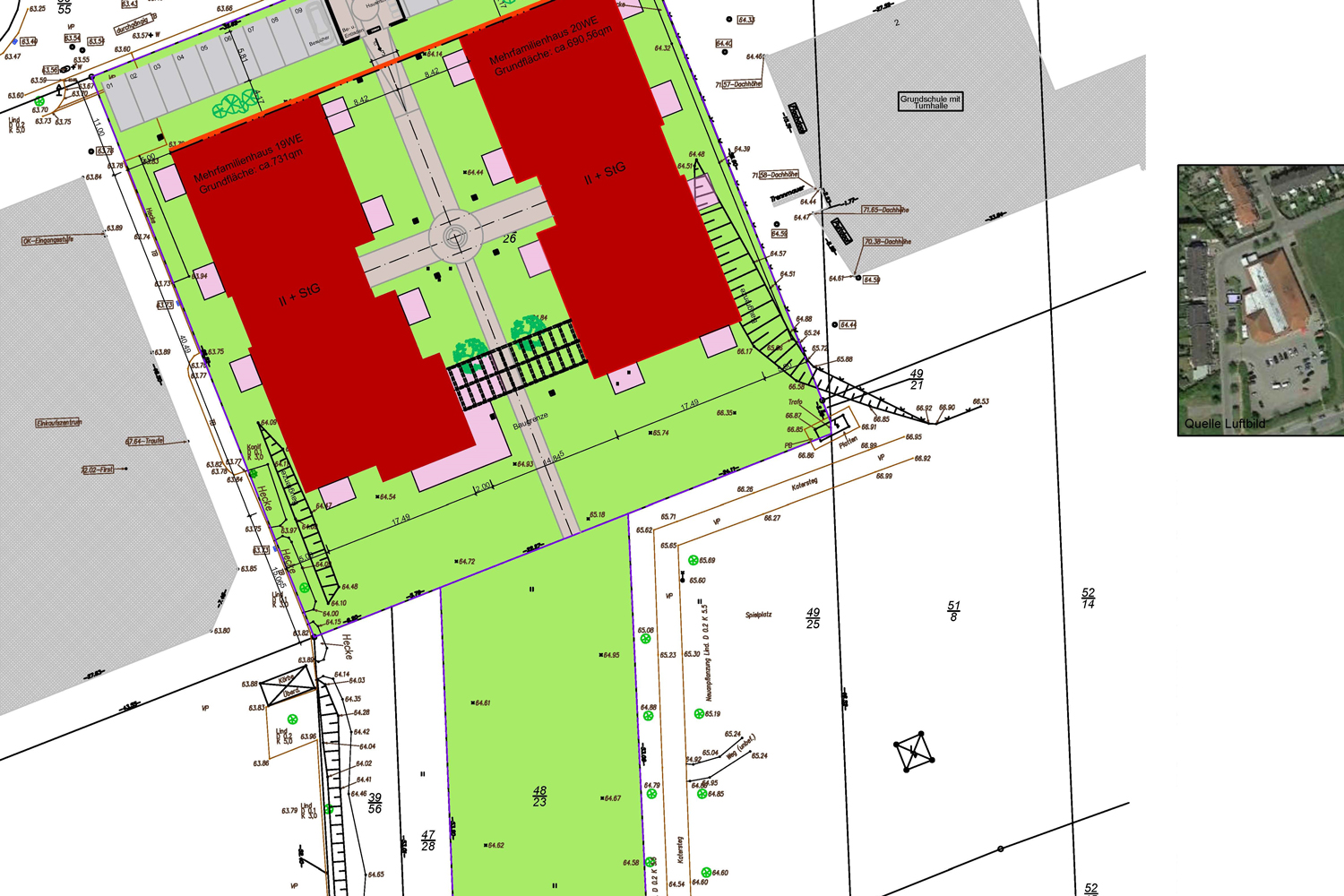

Project development of a modern senior residence complex near Schwerin

This project development comprises an assisted living complex for seniors in an attractive, green setting. The complex will feature two parallel buildings, each with two full and one recessed storey. The site measures approx. 4,120-sqm plot and will accommodate 40 residential units. If required, the development can also be acquired with an operator in place.

The property is located about 6 km west of the city centre of Schwerin.

Price: EUR 7,800,000 plus 5.95% commission (incl. VAT)

Planned area: approx. 2,800 sqm

Construction starts: Autumn 2021

No energy certificate available as this is a new construction project.

(Please quote property reference number 52393 when making your enquiry)

Renovated residential and commercial building in central Braunschweig

This residential and commercial building was originally constructed in 1956 and comprises 13 residential and two commercial units. The half of the penthouse level overlooking the street has been converted into a residential unit and has been equipped with a 21-sqm roof terrace.

This residential and commercial building is located in the centre of Braunschweig.

Price: EUR 3,825,000 plus 7.14% commission (incl. VAT)

Lettable area: 1,297 sqm

Current annual net rent: EUR 138,960

Information acc. to energy performance certificate, residential units: energy consumption 102.0 kWh/(m²*a), energy-efficiency class D, natural gas, built in 1954.

Information acc. to energy performance certificate, commercial units: energy consumption for heating (natural gas) 202.7 kWh/(m²*a), energy consumption for electricity 62.7 kWh/(m²*a), built in 1954.

(Please quote property reference number 52394 when making your enquiry)